More and more companies are bundling internal financial functions and centralising them at a single location internally or outsourcing them to external service providers. This doesn’t affect the responsibilities of the board’s audit committee, but it may make oversight more complex. And while it won’t change the duties and goals of the external auditors, outsourcing will have repercussions in terms of the type, scope, timing and organisation of the work they’re required to do.

The job of the audit committee is to oversee financial reporting, and assure compliance and the organisation’s risk management in the broadest sense. It fulfils this role on behalf of the board of directors, but without relieving the full board of the ultimate responsibility. This remains the case even if financial functions or departments are farmed out to external providers (outsourcing [1]) or internal teams located abroad (offshoring [2]).

[1] Outsourcing involves contracting out business processes to an external partner who delivers the outsourced services in accordance with agreed service levels and costs. The term ‘outsourcing’ merely refers to the fact that services are delivered by a partner outside the organisation, regardless of whether the process takes place within the same country or from one country to another.

[2] Offshoring is the process of relocating tasks to another country where costs are lower. It can involve farming out functions to an internal unit or to an external partner (outsourcing).

Audit committee has to stay informed

Executive management is in charge of actually implementing any outsourcing or offshoring solution. But it’s the audit committee’s responsibility to understand how management has gone about ensuring that the strategy won’t result in any major problems for the organisation.

While an outside company delegated with certain financial functions is responsible for executing the range of tasks in question, this doesn’t mean that ultimate responsibility is transferred from the client to the service provider. If an organisation in Switzerland farms out its entire financial functions to an external company in India, for example, the board of the Swiss client will still bear full responsibility for accounting and financial reporting. The same applies if the Swiss company decides to centralise all its staff at its own service centre in India.

If an organisation is considering outsourcing or offshoring, it’s the audit committee’s duty to inform itself accordingly by questioning the CFO; if circumstances dictate it must interview the CFO together with a representative of the service centre to find out what the implications will be for financial reporting, compliance and risk management. The more serious the potential implications and associated risks are, the more thoroughly and frequently the audit committee should look at the consequences of the move. It’s a good idea to make sure enough time is devoted to this, especially during the implementation phase.

Modifications to internal controls

Since outsourcing and offshoring arrangements generally result in modified processes, adaptations to internal controls are usually entailed. And because a department’s responsibilities are rarely farmed out entirely, it’s crucial to check whether the duties that remain within the organisation will continue to be performed in the same way. Other important questions that should be asked are what processes will change and how, and whether the old controls will still be appropriate under the new organisational structure. Key areas to keep an eye on are the interfaces between the client’s processes and the provider’s processes.

While it’s easy to verify processes when centralising functions internally, it’s more difficult when outsourcing. The degree to which the client company will be able to oversee quality at an outside provider will depend on the terms of the outsourcing agreement. The client will only be able to examine processes at the external provider – either itself, for example by sending in its own internal auditors, or commissioning independent auditors to do so – if it has insisted that the service level agreement include a right of audit clause from the outset, or if the provider grants this right of its own accord.

The client will only be able to examine processes at the external provider if it has insisted that the service level agreement include a right of audit clause from the outset, or if the provider grants this right of its own accord.

As a rule, however, the external service provider will have sought the relevant certification in its own right. In the International Standard on Assurance Engagements (ISAE) 3402, the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB) specifies two types of service auditor’s reports that can be issued on the basis of an examination of processes at a service organisation. In a Type I report, the service auditor will describe and express an opinion on the service organisation’s system, the objectives of its controls, and whether the controls are suitably designed to achieve specified control objectives. In a Type II report, the service auditor will additionally express an opinion on the efficacy of the service organisation’s controls.

Following outsourcing, the scope of the system of internal controls becomes broader, and the controls themselves become significantly more complex. It’s vital to systematically monitor and examine not only internal processes and the related controls, but also processes that end in the interfaces to the service organisation. It’s also important to monitor the quality of the service provider.

Options limited for internal auditors

The internal audit function is a useful tool for the board of directors when it comes to examining certain areas in more depth, and provided financial functions and other services have been delegated within the organisation itself its rights of audit are undisputed. But as already mentioned, the question of whether the internal auditors can also be sent to examine an external provider depends on the terms of the agreement between the client and the service organisation.

Whether they’re working internally or externally, it’s crucial for the internal auditors to have sufficient resources and technical know-how to examine and form an opinion of the specialised arrangements involved in offshoring or outsourcing. Both internal service centres and external service organisations will in most cases operate on a more standardised basis than the departments previously responsible for the financial functions in question. Similar to the external auditor, the internal auditors will have to think about how they’re going to conduct the examination.

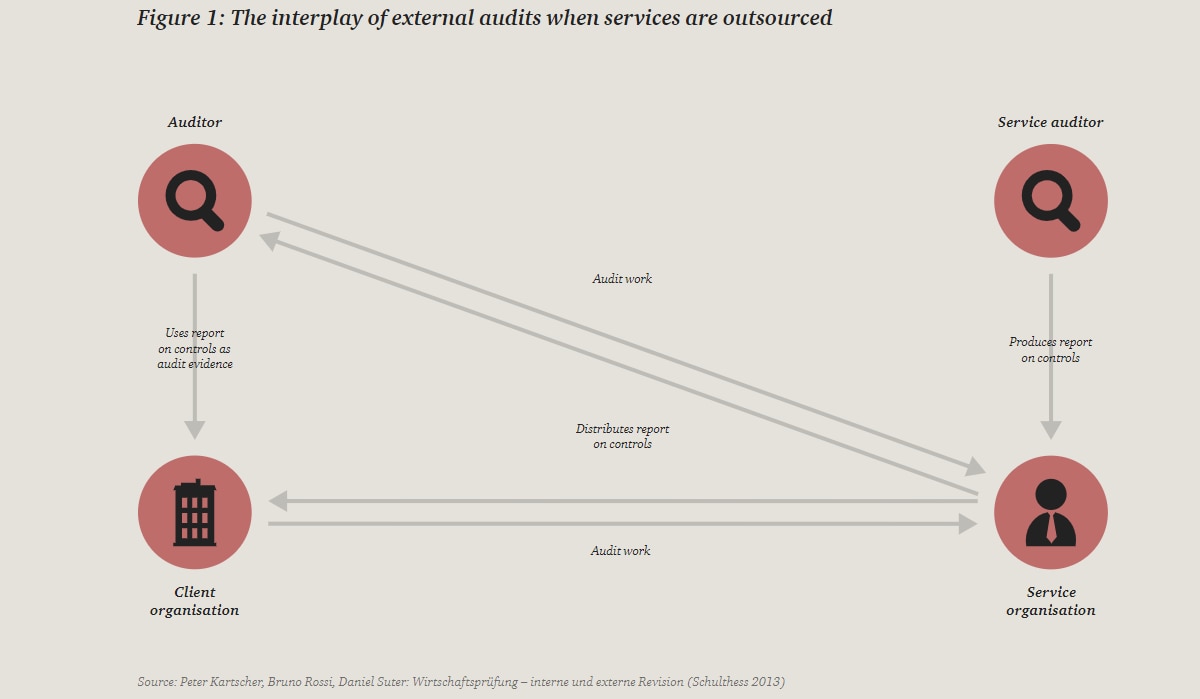

Work performed by an external service auditor

The work of an external auditor will also depend to a crucial extent on whether the chosen solution constitutes offshoring (internal) or outsourcing (external). If an organisation centralises group functions by locating the entire staff responsible in Poland, for example, a large part of the auditor’s work – inspecting records, making enquiries of management representatives and examining the underlying processes and controls with the aim of forming a well-founded opinion – is also likely to shift to Poland. In the case of offshoring it’s important for the external auditor to ascertain whether processes and controls have been standardised and harmonised at the new location, or whether they’re still run in line with the original arrangements. The more standardised and harmonised the processes, the more efficiently and effectively the external auditors will be able to organise and carry out their examination.

It’s also important to consider the distinction between the group and statutory (individual) audits. Statutory financial statements for individual entities are subject to the laws of the country in question, while group financial statements are generally prepared in accordance with recognised rules such as the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) or US Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (US GAAP). If the financial statements for all entities within the group are prepared on a standardised basis at a central location, the most effective and efficient approach will be for them to be audited by a central team at this location. For its part, the central audit team will be part of the audit team that is responsible for the respective statutory audit; in other words, the central audit team will document its work and give the statutory audit team the right to refer to the audit findings to come to its own opinion.

The external auditors are likely to face the greatest challenges in the event of outsourcing. If delegating functions to an outside provider involves major changes, the auditor has to ask not only what has changed and how the new arrangements work, but also who is in possession of the relevant information and how things can be verified. In general it will take longer to establish a stable audit routine.

The more serious the repercussions of outsourcing financial functions and other services are for an organisation, the greater the impact will be on the work of the external auditor. This makes the IASE 3402 service auditor’s reports mentioned above even more important for the external auditors. They’re an important source of information enabling them to assess whether or not they can base their work on the service organisation’s controls.